Article based on subject and findings of the discussion night held on March 12, 2019. Has come into being through the efforts of Arne Steemers (text), Thomas Bollen (images), Valerie Gies (critical review), Nataraj Aravind, Paul Bougie, Lieke van Essen, Jean Ormiston, Rick Peters and Emiel Sietsma.

On the previous discussion night, we set out to explore the question: why is mankind struggling with sustainability if we have all the knowledge, resources, and money needed for it? We came to the conclusion that the story used to promote sustainability is very much based on ideological reasons, which does not appeal to many people. We seem to think that our planet is a very precious and delicate thing, and that we should protect it from the people who try to take advantage of it. It is almost as if we feel sorry for our behaviour with respect to dear Mother Earth. People all over the world are indeed rising in order to stand up for the planet. The reasons for doing so seem evident, but do you know why you are making an effort for sustainability? Are we on a quest for being valuable for society? How could we best tackle the problem anyway? A few insurgent students have joined in an open conversation about their personal motivation and the way they try to make a change.

“We shit in a basin, we flush, and then we don’t care about it anymore.†This is a rather accurate summary of the way we humans use our environment for our personal needs. It is characterised by the wish to fulfil our needs quickly, cleanly, and without any hindrances. Throughout history, one can observe a trend towards increasingly reliable products and services that are now providing a very safe and easy living environment (at least for us Westerners). Taking an evolutionary perspective, this makes a lot of sense. Groups of humans had a greater chance of survival when they were better able to control their environment. Wanting more or wanting to become better might very well be an evolutionary mechanism that is present in all of us. This principle currently seems to be in conflict with our need to think about the long term. Do we need to trade short term thinking for thinking about the long term then?

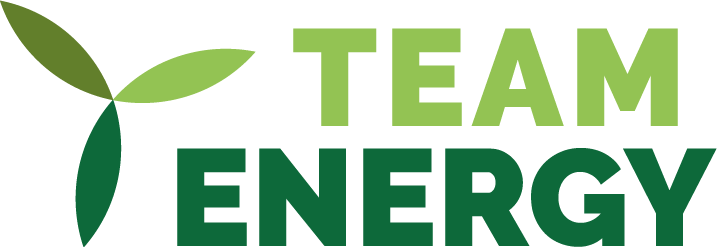

Let us look at the way we tend to address challenges currently. We should note that a problem is something that stands in the way of reaching something else, and that it only exists when you want something. This is shown in infographic 1, a hindrance needs to be cleared in order to obtain a price. Three components are present; a hindrance (a problem), a means of clearing that hindrance (a solution), and a reason for clearing the hindrance (an end). In the case of diesel cars, for example, a reason to use them is our desire for personal transportation, the hindrance is the technical difficulty of production, and a solution to this problem is the engineering of diesel cars. The ‘clearing a hindrance’ way of dealing with challenge might not work for sustainability however, because sustainability can not be ‘achieved’. Sustainability is only a condition to the things that we are actually aiming for. It is not sustainability that we want, it is transportation. The conviction that it should be sustainable at the same time, only means that it should not reduce mankind’s opportunities in the future, and has nothing to do with transportation itself. Simply innovating products will presumably not solve our problem. As Albert Einstein once put it: “we can not solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created themâ€. What way of thinking do we need then?

Infographic 1; clearing a hindrance

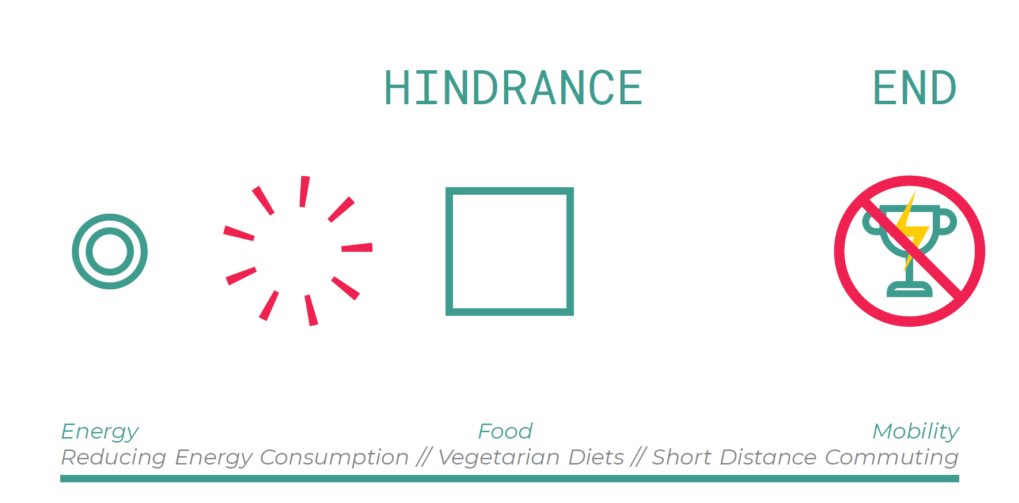

A different mode of thinking would be to realise that there are alternative solutions to reaching an end. Meat substitutes for example, also provide us with essential nutrition but they presumably do so with considerably less impact on the environment. In the face of crisis, we are forced to think of less obvious solutions. Infographic 2 captures the process of finding a ‘work-around’ by bypassing the problem. This is not to say that there are no hindrances to developing, producing, and selling meat substitutes. Rather, it emphasises that hindrances might sometimes block the view to what we are actually striving for. Let us not, however, take this way of dealing challenges for granted, and let us explore another capacity of the mind.

Infographic 2; finding a work-around

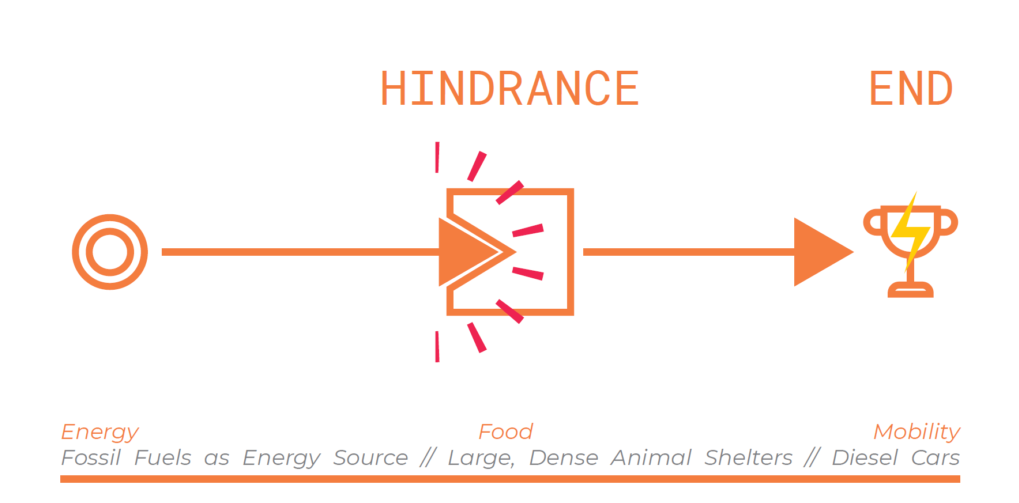

In a third way of dealing with challenge, the ‘end’ takes a central position. Instead of trying to find a solution to a problem, it seduces us to think critically about what we want. Rather than setting goals that will make us happier, ‘rethinking’ is about trying to investigate whether these goals are essential for our happiness. It could as such provide a more immaterial view on the lives of people. You could think of buying less clothes because they might not contribute significantly to your life. Infographic 3 shows what this looks like graphically. Note that the ultimate price, happiness, lies even before the hindrance! ‘Rethinking desires’ does require some self-reflection however, and therefore only works for reducing our own eco-footprint. What if you want to make a change for society?

Well, the number of challenges are abundant. Let us be honest though, addressing them is not easy and requires hard work. The transition towards a ‘sustainable society’, whatever that might be, may very well be the biggest challenge that humanity has ever faced. Although it is doubtful that you will ever be awarded for it, society will certainly reap the benefits. Similar to the way we are reminded of our freedom (only) once a year on National Commemoration Day, people might someday be grateful to the heroes who fought for a healthy planet. Would praise from others not be a vain motive though? Whether we like it or not, all human beings want to be appreciated by others in the end. Is sustainability something that ‘simply should be done’? Are we the ‘unlucky generation’ that needs to clean up? What else is there to gain by engaging in this challenge?

Infographic 3; rethinking desires

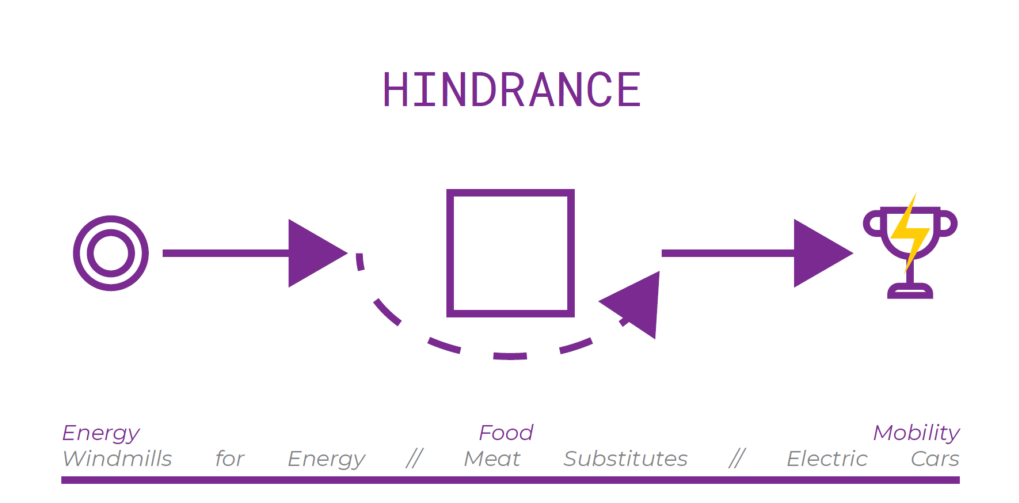

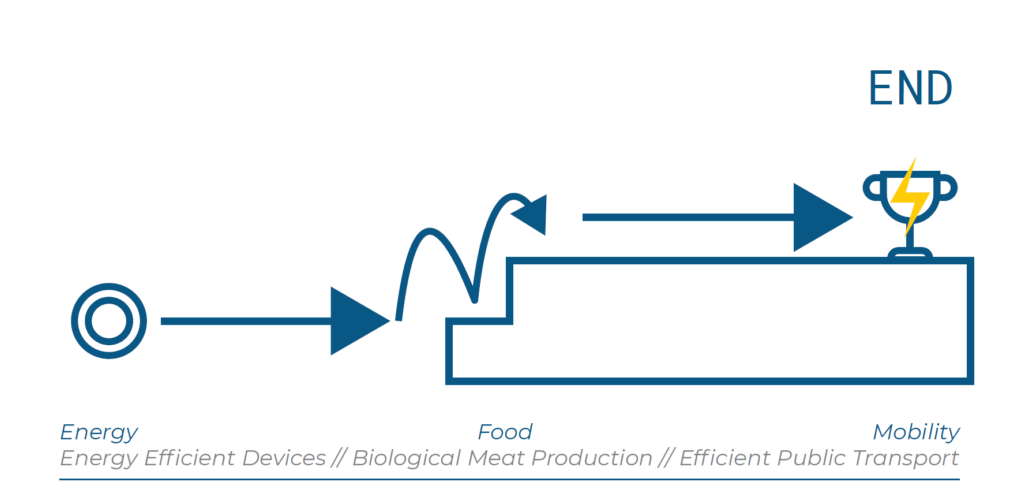

Part of the value of challenges might actually lie in the process. It is easy to forget the satisfaction of solving a problem, when you are still struggling in the midst of it. Societal challenges present excellent opportunities for using all of our wits and capacities. The problem of sustainability does not only require us to exceed our intellectual capabilities, it also enables us to do so. The effort that we have put in solving a problem, partly determines the value of the result too. Would you be proud of achieving something if it were easy? This is illustrated in infographic 4, it takes a few steps before reaching satisfaction. For one thing, there would be no ‘price’ if there were no steps. For another, more and higher steps, increase the satisfaction you will receive when completing a challenge. Why though, should they be challenges of sustainability?

Infographic 4; the bigger the challenge, the bigger the price

All kinds of ethical theories will probably have an answer to that question. We should remember what has been said in the introduction however, ideological reasons do not seem to appeal to people. What does motivate us for making a change then? If we would imagine how we feel in thirty years from now, the best reason for making an effort for sustainability is that we might otherwise regret it. Now we could imagine being born one-hundred years ago. In that case, we might very well have been helping Ford to produce cheap and non-sustainable cars for a lot of people. This shows us that we were not born with the conviction that everything should be sustainable, it is the feeling that has slowly taken shape by finding out about what is going on. We should realise that Henry Ford was actually creating value for society by providing a solution for personal transportation, in spite of the fact that he helped creating the problem that we currently face. Obviously, he also made a lot of money at the same time, and he might not have produced cars if they were not profitable.

Is that immoral though? Should we make an effort for sustainability if there is nothing to gain for us personally? Contributing to the energy transition certainly does not prevent us from profiting ourselves. As we have seen, this personal gain does not have to revolve around money. The energy transition also gives us the opportunity to receive satisfaction by creating value for society. Helping others in order to help ourselves so to speak.

We have hopefully arrived at a more positive attitude towards complex problems. Still some pressing questions remain: what role is there to play for us in this vast and unknown world of constant change? Where should we focus our attention? What challenges can I take on? Do realise that you are not the only one who struggles with these questions. Let us be courageous, and let us refrain from hiding our heads in the sand. We are in this together, and every single one of us has the opportunity to be part of those who will make it work. Once again we feel that we have accomplished quite a lot in just a couple of hours. This may very well be our most valuable conclusion. Some good will, an open mind, and a dynamic evening of listening and discussing is able to give valuable insights. We can make a change, let us not forget to enjoy doing that.